By Kaori Shoji

Want to talk about movies?

From the vantage point of a film writer, the Heisei Era (January 8, 1989 to April 30, 2019) felt like a relationship that neither party had the courage to end. You know – the one where the occasional moments of joy are almost enough to blot out the periodic outbursts of blah. On the plus side, the collapse of the studio system and the rise of the PIA Film Festival’s indies support system enabled young directors to go from “mom, I think I’ll make movies for a living” to getting listed on imdb.com in an unprecedented short span of time.

On the minus side, budgets dried up as the economy sank into the mires of a 20-year recession. Japanese movies lost the clout points earned by the cinematic giants of old, like Akira Kurosawa and Kenji Mizoguchi. The films that came out were drastically reduced in scale. In the meantime, rival filmmakers in China and South Korea emigrated to Hollywood and stunned the world with grandiose, mythical stories funded by mega-budgets.

Still, we kept slingin’ that hammer because deep down in the recesses of our souls, we suspected that this is as good as it gets. Here’s a guide to take you through the most memorable movies (including the bad, the good and the ugly) that adorned the Heisei era – in random order.

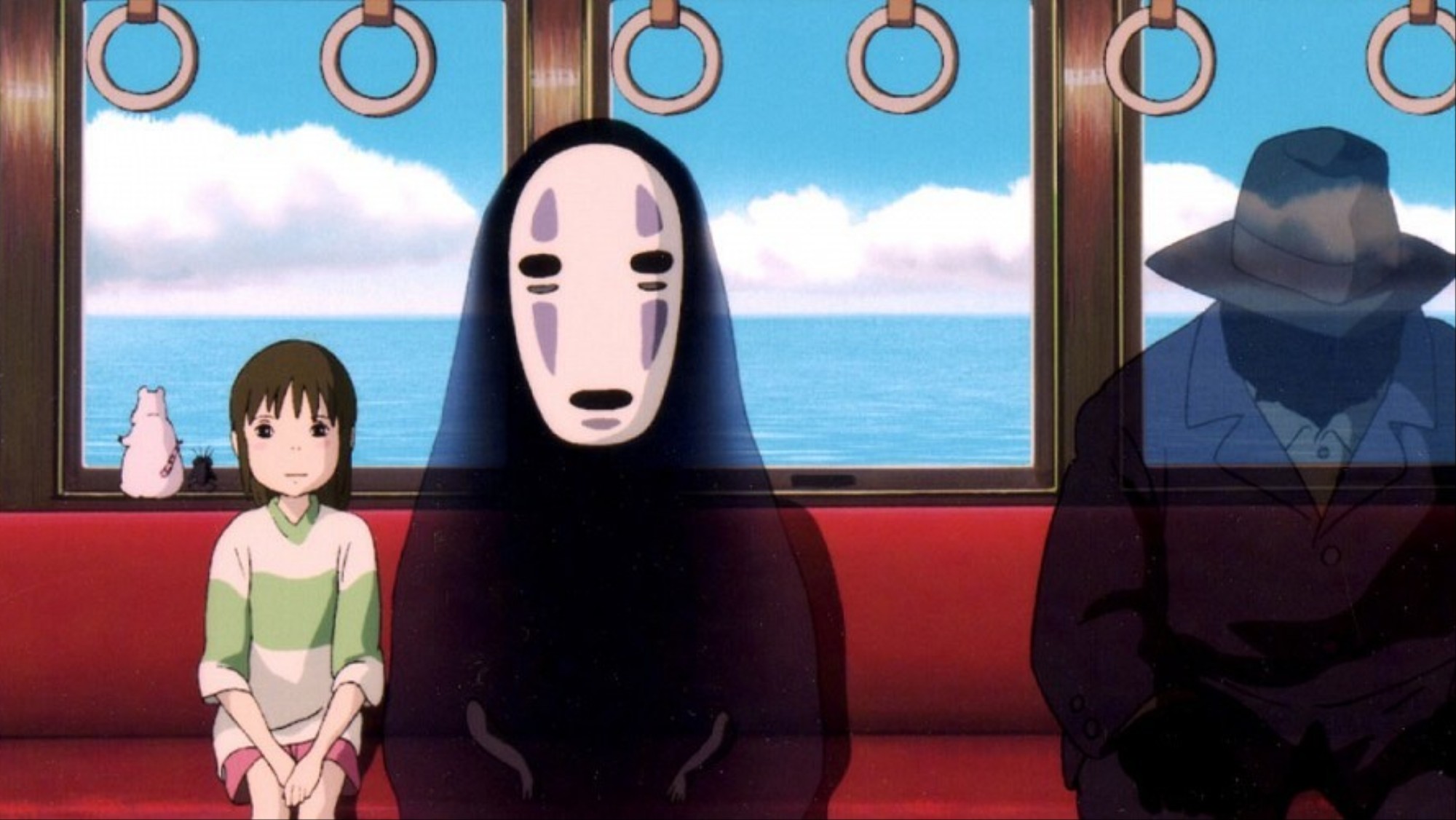

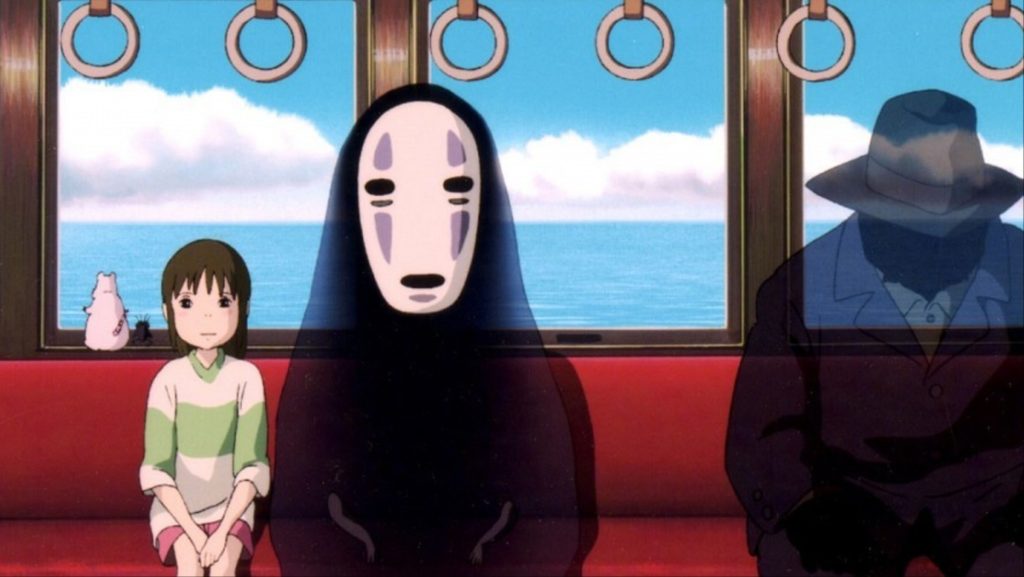

1) Spirited Away『千と千尋の神隠し』2001

Directed by Hayao Miyazaki

In many ways, Heisei belongs to Hayao Miyazaki, who at 78, remains Japanese anime’s biggest influencer. As co-founder of anime production company Studio Ghibli, Miyazaki’s works have always been gorgeous to look at but not always easy to understand; he has always avoided there feel-good formulaic plots favored by of Disney, designed to make everyone feel special and loved. Instead, the grand master of Nippon Anime has loftier plans. Part of it comes from his love of flying – Before WWII, Miyazaki’s family owned and operated a small aircrafts manufacturer and apparently, he was drawing airplanes before he could walk. What Japanese film critics describe as the “soar factor” is prevalent in almost every one of Miyazaki’s films, a sensation of flight, freedom and autonomy as the characters aim for the sky and struggle to gain control over their destinies. In Spirited Away,the soar factor is embodied by a flying dragon, and an impossibly high staircase that 10-year old protagonist Sen must navigate several times each day, if she is to survive and rescue her parents who have been changed into pigs. Spirited Away is a great piece of entertainment but it’s also classic Miyazaki – philosophical and stoic to the very last frame.

2) Minbo『ミンボーの女』1992

Directed by Juzo Itami

In the west, Juzo Itami is best known for Tampopo, a hilarious and sensual celebration of food. Minbo is far less light-hearted.

As the son of eminent prewar filmmaker Mansaku Itami, Juzo had always banked on his rich-kid image and a man-about-town snobbishness, both of which he deployed to full advantage in his films. But Minbo was a different breed. The story of a lawyer specializing in organized crime (played by Itami’s wife and leading lady Nobuko Miyamoto) hired to deal with yakuza (Japanese gangster) thugs, Minbo is dark and accusatory. The yakuza are depicted for what they are: childish, insecure bullies protected by clans interested only in profit (not honor, as most Japanese movies would have us believe). To prove his point, Itami swaps out Miyamoto’s trademark buoyancy for a rigid and sometimes leaden performance and the some of the action sequences seem over-the-top silly. Still, Minbo is probably Juzo Itami’s most important work, not least because it marks a crossroad in both his career and his life. After the release of Minbo, Itami was attacked by yakuza henchmen sent from the notorious Goto clan and got his face slashed up. Five years later, he jumped to his death from his office window. Whether Itami’s death was voluntary or enforced (by Goto’s men) remains an open mystery.

3) The Shoplifters『万引き家族』2018

Directed by Hirokazu Koreeda

One out of 7 children in Japan are living below the poverty line, with school lunches as their main source of nourishment. In Hirokazu Koreeda’s The Shoplifters, that number feels like more. Starring the always watchable Lily Franky and Sakura Ando as a down and out couple raising a 10 year old son in the ramshackle house of an elderly ‘obaachan (grandma),’ The Shoplifters won Koreeda the Palme D’Or at Cannes – the first ever for a Japanese director. The Abe Administration took offense at how Koreeda took the nation’s dirty linen and washed it in public so to speak. But The Shoplifters did wonderfully well at the box office, soaring to number 4 in the list of Japan’s highest grossing films of all time. One of the takeaways of this film is that in spite of their shoplifting, hand-to-mouth existence, the family is united by a fierce loyalty and is somehow, amazingly content – a rarity among Japan’s urban families mired in stress and societal pressure. A poignant and ultimately tragic film, The Shoplifters makes you want to see it again and again.

4) Ichi『殺し屋イチ』2001

Directed by Takashi Miike

Does Takashi Miike have nightmares and if so, what can they possibly look like? As the master portrayer of Japanese stab-and-slash violence, Miike is notorious for his unflinching dedication to drenching the screen in blood and gore. Ichi remains his most memorable work, not least because it stars the internationally respected Tadanobu Asano and the deadpan Nao Omori as rival yakuza henchmen ostensibly bent on revenging the death of their boss. The duo’s real objective however, turns out to be the high savored from killing as many human beings as possible, in the most gruesome of ways. The backdrop is Kabukicho, Shinjuku at the turn of the century, and Ichi’s glamorized violence makes the whole place look dangerously alluring. Present day Kabukicho has turned into a staid tourist trap with surveillance cameras placed in every nook and cranny, to nip violent incidents in the bud, apparently. No worries – even the yakuza go around with eyes glued to their phones.

5) Kamome Shokudo『かもめ食堂』2006

Directed by Naoko Ogigami

Heisei was an era in which many Japanese women categorically refused to get hitched and even more to give birth. The birth rate plummeted to an all-time low of 1.43. In 10 years, one out of five women (and one out of four men) are expected to live out their lives without ever having a partner which may strike the casual observer as a spectacularly tragic statistic. For director Naoko Ogigami however, the numbers are fodder for her particular genre of filmmaking. Kamome Shokudo is her breakthrough work that deal with a trio of single women who come together in Helsinki. One of them, Sachie (Satomi Kobayashi) runs a local diner and the other two (played by Hairi Katagiri and Masako Motai) decide to work there as well. The utter absence of emotional drama (but an abundance of great food) is incredibly healing as you realize that Japanese women may have more freedom and control over their lives than we thought. Best line: “Onigiri is the soul food of Japan.”

6) Zan『斬』2018

Directed by Shinya Tsukamoto

Shinya Tsukamoto is a weird and wonderful film buff. For the entirety of the Heisei Era, he has acted, produced and directed his own films – always on a minuscule budget and a minimal number of staff. He even nabbed a part in Martin Scorsese’s Silence (for which he auditioned along with everyone else), prompting the great Scorsese to seek Tsukamoto out on set and shake his hand.

Last year, Tsukamoto came out with Zan which he shot in less than a month and starred as a wandering samurai in the last days of the Edo Period. The film is brilliant for two reasons: 1) it highlights the samurai class as reluctant murderers who must cut people up to prove themselves, and 2) it shows up the brutally labor-intensive, muck raking poverty of late 19th century Japan. In the midst of the shit-logged ditch water however, you can almost glimpse that gem of hope. An unforgettable cinema experience.

7) Tokyo Sonata『トウキョウソナタ』2008

Directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Years have passed since Kiyoshi Kurosawa replaced Akira as the pre-eminent Japanese filmmaker with that surname. Though Kurosawa’s main turf is horror, (Cure, anyone?) Tokyo Sonata is arguably his best and most accessible work, drawing an unexpectedly stunning performance from former pop idol Kyoko Koizumi.

Koizumi plays housewife Megumi, who is ambivalent about her stay-at-home existence in the burbs while having no idea how to break out of her shell. Her husband (Teruyuki Kagawa) is a sarariman (salaryman) who has recently been fired from his job, but pretends to go to work every morning in his suit and tie. The couples’ two reticent teenage sons have plans and desires of their own, of which their parents know nothing. Each of the family members seem to be dancing to a different tune, audible only to themselves until one day, their hidden urges come tumbling out. A haunting beautiful story that amply illustrates the dreariness of Japan’s two-decade long recession.

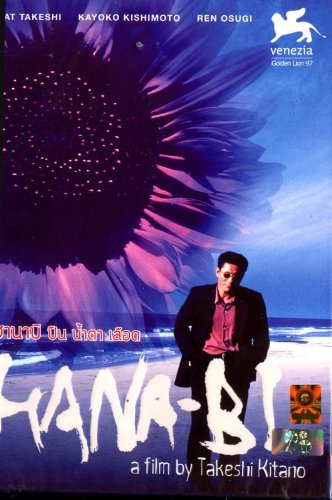

8) 北野武監督

HANA-BI 1997年

Say what you like about comedian and filmmaker Takeshi Kitano, but there’s no denying that for about 20 years in the Heisei period, the man was the closest thing Japan had to a living deity. The man has a violent streak, as demonstrated in the 1986 attack on the offices of papparazi rag “Friday” for which he was arrested and found guilty (but got off with a suspended sentence). In 1994, a motor bike accident that would have killed another man landed him in the hospital for 6 months but before he got out, he went on the air and cracked jokes about his horribly disfigured face.

In the Heisei era, Kitano made some unforgettable movies but HANA-BI, (meaning ‘fireworks’) is a masterpiece. He directed, co-wrote and starred as Nishi, a cop who has just lost a young son. The tragedy causes Nishi’s life to spin out of control, as his wife (Kayoko Kishimoto) is hospitalized and his buddy Horibe (Ren Osugi) is shot by a perpetrator. Later, Nishi quits the police force to takes his wife on a trip, intending to kill her before putting a bullet in his own head.

Though Kitano has always worked in comedy, he is rarely verbose and HANA-BI is amazingly reticent. The absence of explanatory dialogue matches the extraordinarily lovely visuals, drenched in dark blue and gray tones as the story traces the graceful arc of Nishi’s downfall.

9) “Helter Skelter” 『ヘルタースケルター』2012

Directed by Mika Ninagawa

Mike Ninagawa may have been born with a silver spoon but her talent (and personal struggle) is achingly real. As the daughter of Japan’s foremost theater director Yukio Ninagawa, Mika’s life was both charmed and cursed. Dad’s glorious reputation preceded her everywhere she went so perhaps it was natural for her to choose photography and film instead of the stage. Helter Skelter is her second feature and stars the enfant terrible of the Japanese film industry Erika Sawajiri, as a nymphomaniac actress who lives in fear of losing her beauty. To prevent this from happening, the actress periodically goes under the knife, endangering not just her health but her sanity as well. Helter Skelter is audacious, brilliant and gorgeously shot – and an astute observation of fame and celebrity-dom in Japan’s youth-obsessed media industry.

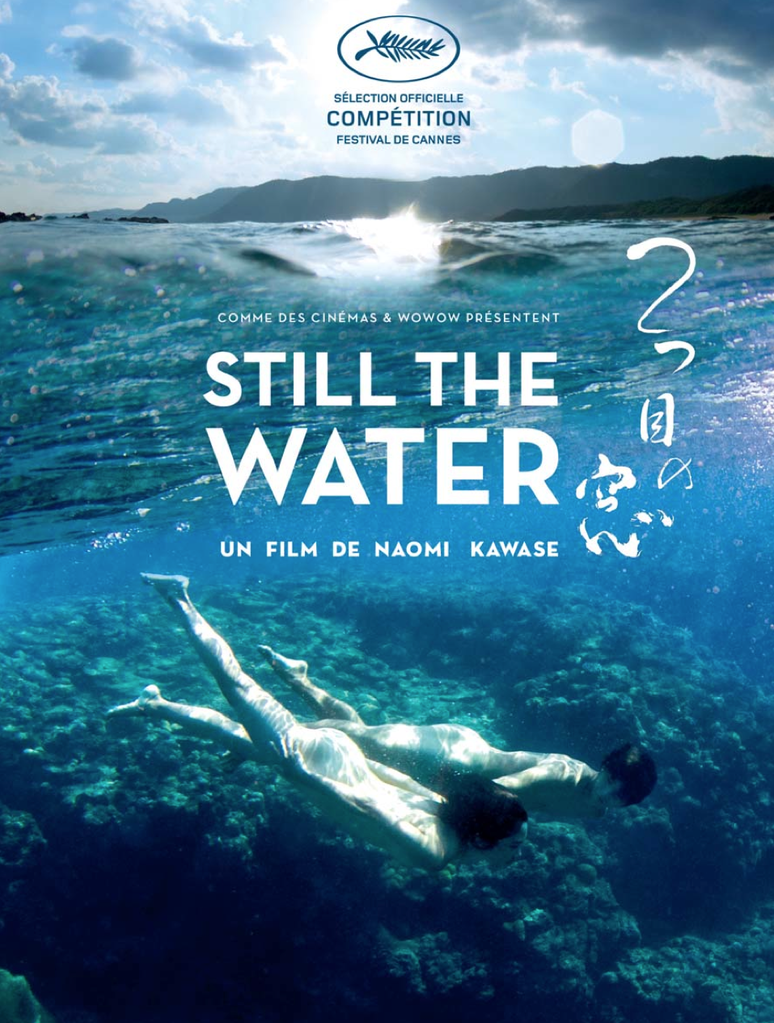

10) Still the Water 『2つ目の窓』2014

Directed by Naomi Kawase

Naomi Kawase had a chaotic upbringing –her parents more or less abandoned her when she was a baby and the filmmaker was subsequently brought up by a relative. In interviews, Kawase has said she has tried to understand her life by making films about families and indeed, her works show a special fascination (or obsession) with the family dynamic. Still the Water feels especially intimate – a coming of age tale set in gorgeous Amami Oshima island off the coast of Kagoshima prefecture. Two teenagers (Junko Abe and Nijiro MurakamiI) struggle with their roots as their parents fumble about, trying to come to terms with their own identities and personal desires. Miyuki Kumagai plays the island ‘yuta’ (shaman) who must face her own imminent death by cancer, as her family resents her apparent powerlessness over her fate. A film that feels like an solitary, introverted vacation by the beach.