What do you know about poverty in Japan?

What demographics constitutes “the poor” here? And how do poverty levels compare with that of the United States, for example?

Martin Fackler in the NYTimes writes: “Many Japanese, who cling to the popular myth that their nation is uniformly middle class, were further shocked to see that Japan’s poverty rate, at 15.7 percent, was close to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s figure of 17.1 percent in the United States, whose glaring social inequalities have long been viewed with scorn and pity here.”

Fortunately, Japan’s first food bank, Second Harvest, had been on the job since 2000 – a time when the very idea of a food bank was completely alien to the

country. By 2009, the NPO estimates that yearly it serves over a third of the 650,000 Japanese that lack “food security”.

(As an aside- there are several food banks in the U.S. which use the same name, though none of them are affiliated with Second Harvest Japan).

Charles E. McJilton, founder and CEO of Second Harvest Japan, stressed that he doesn’t like to characterize what he does as “helping people”, but rather “providing the tools and assistance to people in need” because ultimately — “people can help themselves”.

McJilton himself appreciates the opportunities others gave him to succeed, having brought himself out of less than auspicious beginnings; by the time he was 16, he was a drug addict and an alcoholic. As a way to “give back”, his counselor recommended he start volunteering at a crisis clinic; “one aspect of volunteering is certainly doing something good”, he notes. “But another aspect is seeing for yourself, what is going on in society, and making your own judgement about what is going on.”

He would later put his values into play in a more radical way- by living along the Sumida river, where many homeless reside in make-shift tents or even cardboard boxes. “I had a lot of head knowledge about homelessness, and poverty”, he says, but at the same time desired to really “live out” his values. He initially resolved to stay for 3 months; he left after a year and 3 months. “When I started living along the river, poverty and hunger were no longer a theory to think about but a reality to live with each day”.

However, McJilton points out, “poverty isn’t just about homelessness” – one of the most prevalent misconceptions about poverty in Japan. While Second Harvest does serve the homeless community (every Saturday in Ueno park) the aid goes to mostly welfare institutions (such as orphanages, hospices, battered women’s shelters, etc.) and individual families, as you can see in the chart below.

For the relative wealth of the country, the number of people who lack food security is immense; but so is the amount of food that goes to waste in Japan. Almost a third is thrown out for not meeting the fastidious requirements of the Japanese consumer (the “3P’s” , according to McJilton: pristine, perfect, and pretty).

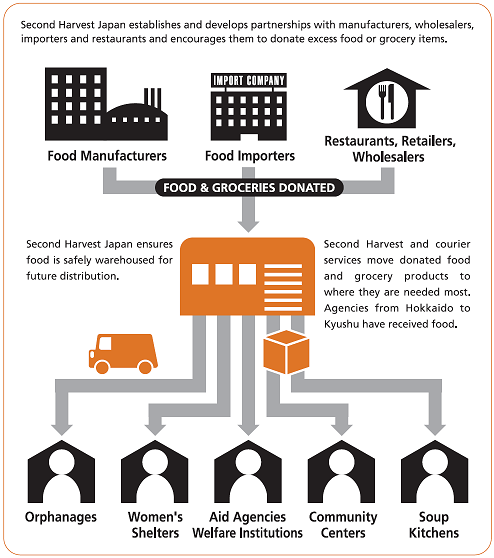

The following chart, found on Second Harvest’s website, explains how a food bank works:

“Second Harvest Japan collects safe-to-consume food that became unsalable for various reasons from food companies and individual donors. Then, we distribute the food to those in need such as low-income households and single mother agencies. “

Second Harvest Business Model

In a country with so much food waste, the potential for relocating resources is frustratingly clear. Nevertheless, McJilton had a tough time selling the idea in Japan to both donors and recipients. As its existence belies the nationalistic myth of an egalitarian Japan, poverty is a touchy subject with the Japanese; and in a society where the human relics of World War II still grace us, their spines sharply contorted due to malnutrition and hard labor – so is food waste.

As over 600 companies have donated food since 2002, McJilton seems to be successful in navigating these delicate topics. He exhibits a good understanding of the specific concerns for both parties. Corporations, which often end up throwing away perfectly good food, worry that the donations will be re-sold or that the food would go bad before distribution and make people sick. On the other hand, those in need have a great cultural aversion to accepting aid; they also are wary that they will be later charged for the food, or receive spoiled goods.

“We have never gone out and asked for food or money.”

It may seem like a strange strategy for attracting donors, but McJilton insists that this policy has helped retain clients and improve relationships. For companies, there are incentives to donate; rather than paying for discarded food to be destroyed, a company can save 80 million yen a year by donating. They also receive free distribution of their products to potential new buyers.

The food bank, of course, has certain standards for food donations: no dented cans, no expired food, nothing opened, etc. A letter of agreement between the food bank and the donor spells out the different responsibilities of both parties. McJilton identifies two reasons that this works better than the traditional method of requesting donations; first, the written agreement ensures that there is equality between the two parties. “We believe if we go out and say ‘onegaishimasu!’ to ‘those above’, there is a great potential for us who are giving out to be ‘down below’. You, (donor), have an excess resource, a tool–lets make a match.”

Secondly, McJilton also observes that the companies who recognize the benefits of a long-term business relationship with Second Harvest keep coming back. Those, however, who give because they sense obligation or guilt? “They might come back one or two times”.

“(McJilton’s) belief that all relationships should be based on equality resonated with me. He doesn’t beg for donors, nor does he feel elevated due to his public service. He simply believes in equal footing in his partnerships. How often do we bow before others or think of ourselves as doing someone a favor?” – Soness Stevens, Living Visions

Second Harvest and Tohoku

The earthquake has spawned an additional food crisis in the radiated and partially-evacuated North, a challenge that adds to the non-profit’s ambitious goals. Though Second Harvest does not usually buy food for distribution, since the March 11th earthquake the organization has been spending up to 3 million yen a week on food. McJilton laments that the amount of food donated could certainly feed Tohoku; however, doing business in Japan of course means following the customs, and in the case of disaster relief, this means providing identical and equal portions of food to all who receive. In order to ensure this is so, the food must actually be bought.

Their recent newsletter states that Second Harvest is “planning to build a local food bank network to provide long-term support in the region.”

If you are interested in donating or volunteering, please check out Second Harvest’s volunteer schedule. Volunteers are always welcome!, and so is good food.

[…] Japan’s First Food Bank: Applying Japanese Efficiency to the Problem of Hunger (japansubculture.com) […]

Hello,

My name is Jesse Lee Rhodes. I will be moving to Chiba Japan in about 6 months from the UNited States. I will be living there. I want to ‘help’. I noticed this wonderful work and I would like to offer my support.

Please contact me at the above email address.

Thank you,

Jesse Lee Rhodes

You should probably contact the Food Bank directly. If there is no contact number available on the home page for them, let me know and I’ll get a contact number for you.

I heartily support Second Harvest. I volunteered there, along with my son. Japan’s uchi/soto culture, which basically charges each group to take care of its own, has many advantages. However, one disadvantage is that people who slip through the cracks–who are not clearly tied to a strong, supportive group–find few organizations offering help. Second Harvest is particulalry helpful to such people.

I think it’s great that you not only support them but you volunteer for them as well. My kudos and respect. 感謝!

Thank you so much for sharing this, JapanSubCulture. A most inspiring aspect of Japan’s Sub-Culture!