The Japanese family is in trouble. But then again, that’s nothing new. Traditionally speaking, family ties are the most sacred of Japanese relationships. But I’m not so sure, it seems like a lot of Japanese — especially parents — have historically and consistently treated their offspring like shit. Time and again, they’ve shown how family means diddly-squat in the face of work/profit/duty. Take for example one of the most most-loved women in Japanese history — 17th century nanny Masaoka. When assassins sought to kill her clan lord’s baby son, Masaoka switched him with her own child, who wound up murdered. She’s considered the towering monument of Japanese womanhood. As for fathers, they’re historically famous for butchering each other’s sons (not to mention wives, sisters, courtesans, and anyone else who stood in the way of expanding the clan and pledging loyalty to the powers that be).

Such stories abound in the nation’s history, and the logic supporting that legacy carries right over to present day. The majority of white collar workers find it really, really hard to put their family before work and social commitments — a national character trait that’s embedded in the social system.

Not surprisingly, the literature surrounding the Japanese family is apt to be either negative, sad, tragic or all three. The rock bottom birth rate compounded with the high divorce rate says much about the modern Japanese love relationship, but the parent-child issue is worse. The number of child abuse cases are way up — in 2013 the number of abuse cases handled by child consultation centers rose above 70,000 — along with the child poverty rate: one out of six kids in Japan are going hungry.

The older generation isn’t faring much better. Baby boomers in their seventies have an average 20 million yen stashed in their savings account while their middle-aged children are scrambling for ways to dodge the cripplingly high inheritance tax, long before the parents are dead. Try looking for love somewhere in this icy tundra and you’ll end up with not much more than a pocket calculator and a self-help manual.

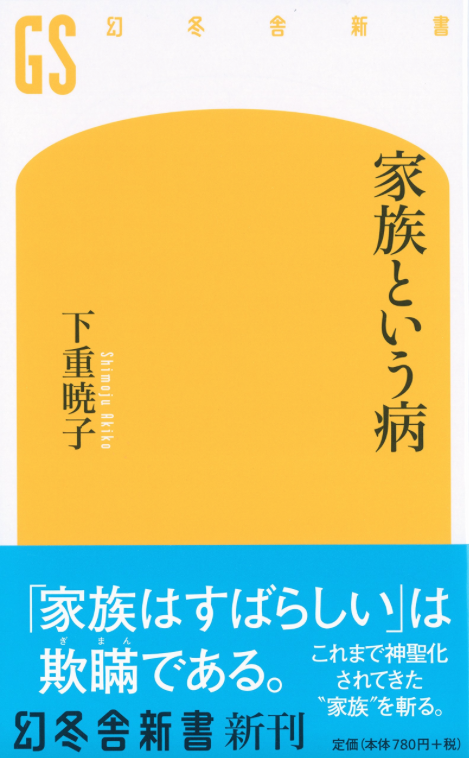

Under the circumstances, now is a good time to talk about a book called “Kazoku to yu Yamai” (The Disease Called Family) by Akiko Shimoshige. It’s flying off the shelves (that is, for a non-manga publication) and over 250,000 copies have sold since the book first came out in March.

Shimoshige — a former NHK newscaster whose father was an elite in the Japanese military during WWII — lets rip with her deep hatred and mistrust of the Japanese family in general, and the complicated but none too warm feelings she has for her own family in particular. By her own account, Shimoshige had never lacked for anything, and at a time when other girls in her generation had little choice but to marry and become the dreaded Japanese housewife, Shimoshige got herself a solid education and a career in the media. She married a journalist and had no kids, which left her free to pursue her work and sow the contempt she felt for “ordinary Japanese people whose new year cards are printed with the latest photos of their families” — a custom she feels should be abolished immediately.

Contempt seems to be the operative word in Shimoshige’s book — start to finish, she looks down on the Japanese family in any way, shape or form. When you consider how the Japanese thrive on being told how awful they are (another national character trait) it would seem she’s adopting just the right tone for literary success. “Kazoku to yu Yamai” tells you that Japanese fathers are narrow-minded and self-seeking, Japanese mothers are downtrodden and willfully uninformed, and that Japanese children are victims of repressive families and antiquated schools, both hell-bent on fostering mediocrity. The hated symbol of the Japanese home, according to Shimoshige, is the “kotatsu and mikan” (the kotatsu is a heated low table with a blanket to keep out the cold, and mikan are mandarin oranges. Japanese families have traditionally convened around the kotatsu to talk, eat mikan and keep winter woes at bay) set up as fostering laziness and bad habits.

As far as books about family psychology go, “Kazoku” doesn’t offer much in the way of knowledge or insight. It’s almost exclusively based on personal experience, and boils down to the fact that Shimoshige is from a very privileged background. While professing to dislike her father for his militaristic views and outdated elitism, she devotes a huge chunk of the book to his career and subsequent downfall after being condemned for war crimes during the Tokyo Trials. Her father lost his job, and apparently couldn’t quite grasp the fact that he was no longer a decorated military brass, with a legion of underlings at his beck and call. Her mother devoted her entire life to the care and support of this man, and Shimoshige laments that with her brains, her mother could have done so much more. Other adults in her family were academics and corporate bosses, and Shimoshige cites them as examples of how intelligence and success can liberate the Japanese from the bonds of the family. Still, she writes with a touch of loneliness: “No one in my family has ever asked me for help. They were too afraid of being a burden on me.”

Indeed, the Japanese way of expressing love is to lift that burden, and according to Shimoshige the more intelligent a person is, the less dependant they are on their families. Maybe so – consider Yukio Mishima who committed seppuku on national television without letting his family know about it. But imagine their aftermath. Imagine the burden of having to live with such a thing, weighing on the mind year after year.

Personally, I’ve always had a thing for kotatsu and mikan. And hey, is it such a bad thing for people to be a burden on each other? In the US, people are giving out free hugs on street corners and parents are exhorting each other to talk to, and play with their kids, every single day. Academy Award winner J.K. Simmons said as part of his acceptance speech: “Call your mother” and the guy is 60 years old. Meanwhile, in Japan the fashionable thing is to not hug your kids, but give them video games and strap them to car seats. If family is a disease, then Shimoshige should rest easy — most of us here are free of the virus.