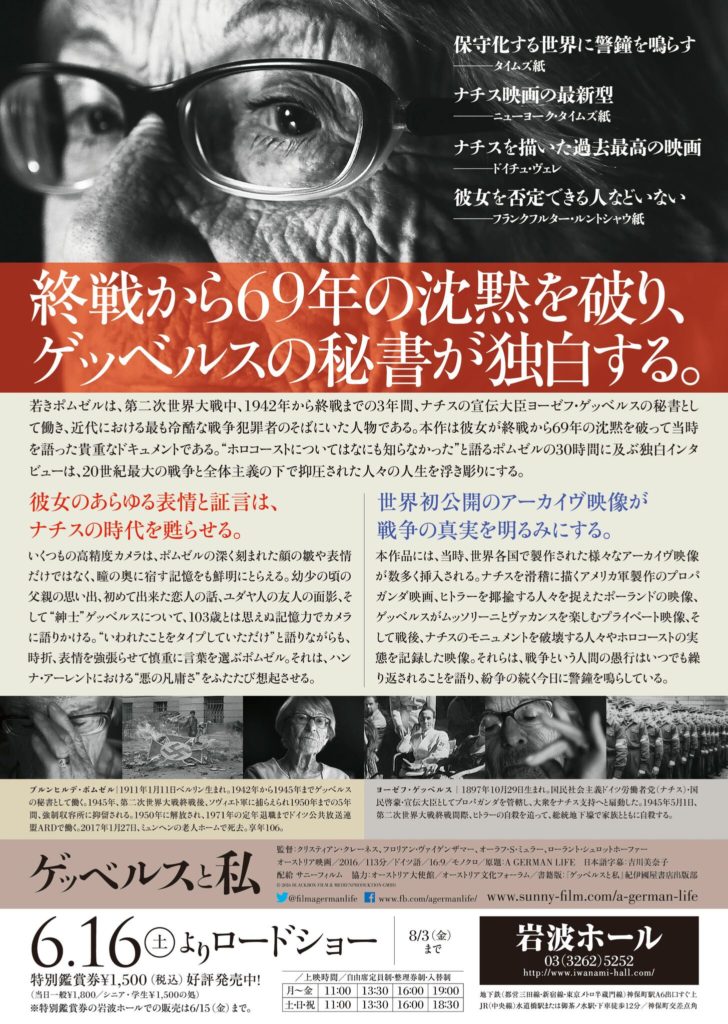

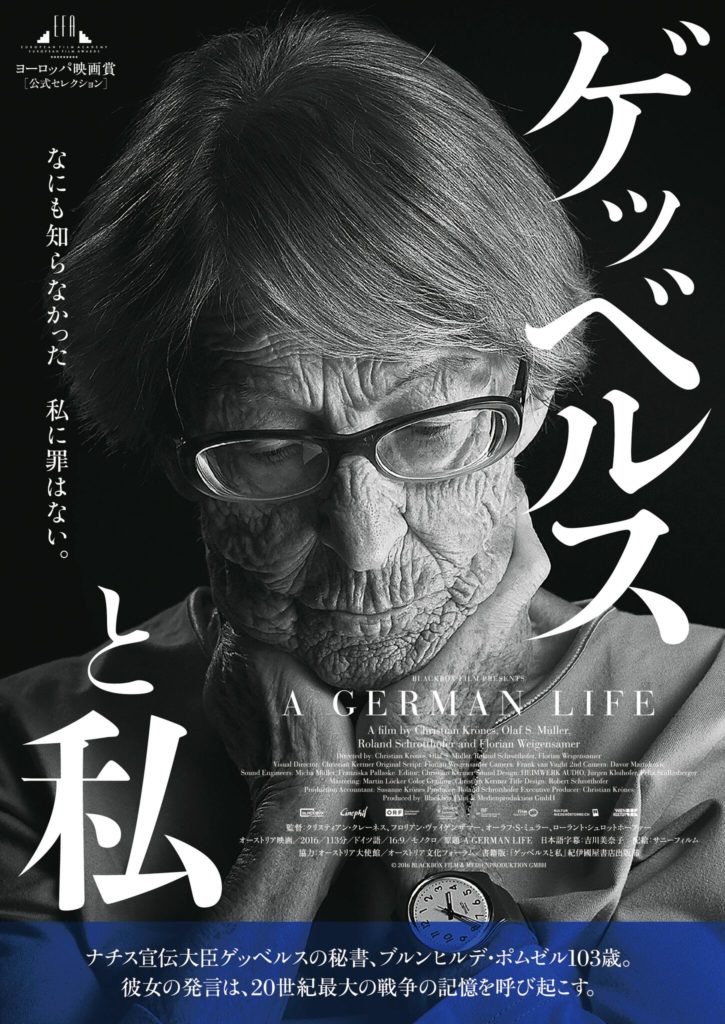

She’s old, really old. You could describe her as an ancient relic. But at 103 years old, Brunhilde Pomsel seems strong, confident, even blase. Pomsel is the centerpiece of the stunning documentary, A German Life (released in Japan as Goebbels to Watashi ) in which she recounts the years she spent in the employ of the Third Reich, as a personal secretary to Joseph Goebbels. Shot in a gradations of black and gray, A German Life, highlights her still soft hair and the brightness of her eyes. What you’ll notice however, are the deep crevices crisscrossing her face, an incredibly creasy visage that make her look like some kind of exotic deepwater fish. Only once does her confidence falter, and that’s when she’s asked to recall whether she was aware of the existence of the concentration camps. “I didn’t know it,” she says but her voice lacks conviction. “I wasn’t guilty of that, but if I was, then the whole of Germany during the reign of the Third Reich – was guilty.”

The film will resonate with many viewers in Japan, not least because Germany was an Axis partner in WWII, but for the radical difference in the way the two nations have dealt with their wartime legacies of shame and humiliation. For many Japanese, the war years are a receding memory, most often romanticized and tinged with sentiment, as in The Eternal Zero. The stories told in the media or retold by our elders, have always varied little, summed up in a singular theme that combines victimization and valor. In this theme, the atrocities committed by the military in Asia, are glossed over. After all, the Japanese starved, Japan went through unspeakable deprivation, was relentlessly firebombed and then the Japanese people had two nuclear bombs dropped right on their heads for good measure. Whatever terrible things the Japanese military did in China and Southeast Asia, was paid for with our own suffering. We’ve checked off the items on our rap sheet of atonement. So let’s agree to sweep all that stuff under the futon and get on with the business at hand, shall we?

This particular logic (or lack thereof) has come to define the collective memory in the 7-plus decades after the Japanese surrender. It wasn’t really our fault, but the fault of the entire era, and the unstoppable war machine! Compare this mind-set to Germany. They also suffered from the air raids and bombings and went through hell. But they are also a people unafraid to rub their faces in the shit pile of defeat. To this day, they are still examining what exactly happened, and why. New revelations of Nazi atrocities are being unearthed all the time, to be dissected and discussed. The Germans have not averted their gaze from the past, rather they’ve been pretty relentless in their cause to track down and then lay bare the gruesome details of their own crimes. Consider the meticulously categorized displays at the Auschwitz Memorials. The unforgiving precision that characterize the guided tour of those Memorials. The sheer number of movies and documentaries that have come out about the camps and the Third Reich. Or the revived public interest in Sophie Scholl, the young political activist who was guillotined for her fierce anti-Nazism.

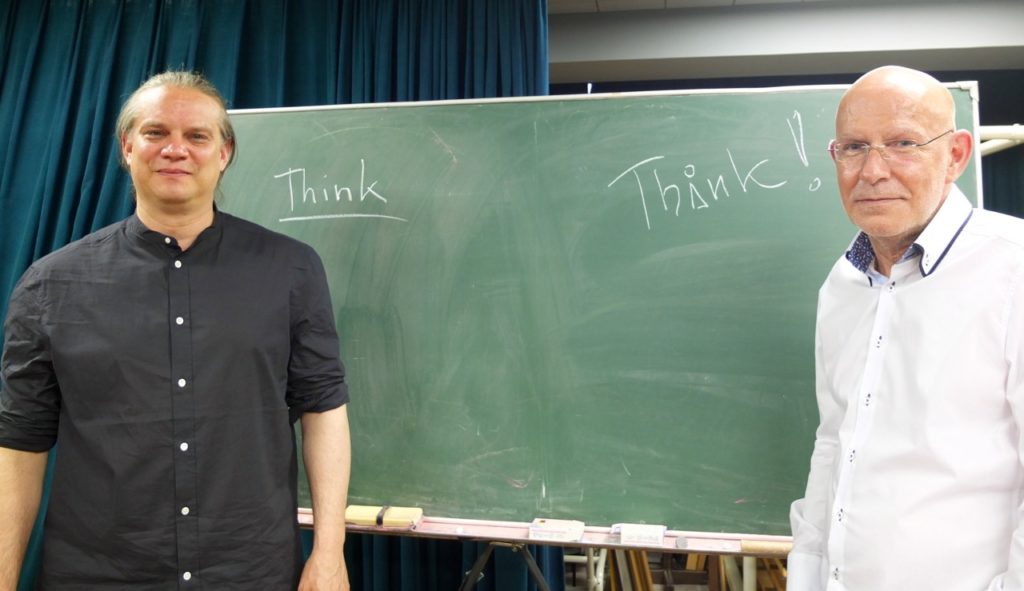

“For all that, I believe that Germany is experiencing an eerie deja vu of the Nazi years,” said Florian Weigensamer, one of the four-man directorial team behind A German Life. Weigensamer was in Tokyo to promote the film, along with another director Christian Krones, who is also the founder of Blackbox Films and Media Productions. Blackbox engineered the whole endeavor that is this movie and other award winning documentaries. Krones and Weigensamer have been colleagues and friends for over 20 years and they’ve dedicated a good chunk of their professional lives to the excavation of some of humanity’s most complex problems. (One of their recent projects is a documentary called Welcome to Sodom that examines Ghana’s burgeoning waste problem, born of discarded home appliances.)

Krones is the oldest and most experienced member of Blackbox but he stresses that there’s no corporate hierarchy at work. “I like to take a democratic approach to filmmaking. No orders are issued top-down. There are no one-man decisions. We hold extensive meetings and discuss the film process every step of the way, like a real democracy.” And he added with a chuckle, “We do this because the film industry tends to be very dictatorial and we are very sensitive to anything that smacks of dictatorship!”

Blackbox is an Austrian company as are Krones and Weigensamer. Because they don’t carry German passports, the pair say that their gaze on WWII and the Nazi atrocities are a little distanced. “We were both born many years after the war,” said Weigensamer. “And growing up, I remember my own family didn’t really talk about the war unless it was to say that we were victimized. In this way, I guess we are a lot like the Japanese.” In 1938, Austria was forcibly annexed to Germany in what was known as the Anschluss, and according to Krones, it “laid the groundwork for turning a blind eye to Nazi atrocities. The Nazis held Austria in a grip of terror and the Austrians felt powerless. They descended into denial, and most people just tried to make it through the war years without getting killed.” Weigensamer nodded in assent, but said, “And now we are seeing the rise of neo-Nazis, and the end of tolerance for refugees and outsiders.” Indeed, Krones said, “When we first started filming ‘A German Life,’ I thought, we would be talking about something that was past and over with. Now I feel like I’ve gone back in time, and traveled to a future where the nightmare is beginning all over again.”

As for Brunhilde Pomsel, she comes off as neither a tragic heroine or an evil monster but a woman with exceptional secretarial skills and a breathtakingly banal personality. Astonishingly, before taking up her duties for the Third Reich, Pomsel had worked in a Jewish insurance company in Berlin while having a side gig in the afternoons working for an official in the Nazi Party. Her lover and fiance was half Jewish. (In the film, she has a silver band around her ring finger.) He was killed in Amsterdam in 1942. Her best friend was a young Jewish woman named Ava, who died in one of the camps. All around her, Jewish people were being taken away, ostensibly to a place of “re-education,” and she didn’t think to question what this may really mean. Her take on Joseph Goebbels is that he was “so dapper, so dashing! The cut of his suits was perfect.” Pomsel even remembered how Goebbels’s children would come to pick him up at lunchtime so that they could all walk home together for the midday meal.

Pomsel apparently compartmentalized all that into her life, and shut out whatever she deemed unworthy of attention. She never stopped to examine the contradictions of her thoughts or her actions. She simply wanted to perform her duties well, and then go home.

“The thing is, she was very likable,” described Weigenhamer. “She was articulate, self-sufficient and loved going to the theatre. She took very good care of herself and liked to have a good time. At first I thought I liked this woman but the more time I spent with her, the more I got to hate her.” Krones said: “What struck me was her incredible selfishness. I honestly got the feeling that she was alone because she didn’t want to share her life with anybody. She enjoyed living. But as in the war years, she wanted her life to be hers alone. And this mentality, this wish to shut out others – is part of what made Hitler successful.”

Brunhilde Pomsel died last year, at the age of 106.

The film opens in Japan on June 16th. Editor’s note: ironically, the current government of Japan doesn’t only have a desire to revise history and bury Japan’s war crimes, the Prime Minister and his cabinet have a great fondness for the Nazi Party and their political strategies. History does repeat itself.

The Jewish hatred against Whites and their anti-German history forging will never end, hm?

Friendly reminder that the holohoax is a Jewish lie 😉

Here’s a friendly reminder to go back to elementary school and study basic grammar, my feeble-minded pal.