In honour of Japan’s Celebration of Cinema Day, December 1st, we’ve reposted some reviews and articles on classic films. Some good, some bad, some epic. Coming soon, our article about the Hollywood remake.

In my mind, anime can be categorized into two varieties: action-based/artistic ones, and teenage school kid soap operas. The former is what western critics typically consider to be “good”, anime like The Cat Returns or Cowboy Bebop, which contrast beautiful hand-drawn landscapes and well-trodden stories with violence and distinctively weird characters that could only be thought up in Japan. Along with Akira, Ghost in the Shell is considered one of the big grandfathers for sci-fi anime, and more importantly black leather-clad sci-fi such as The Matrix. Even in the ‘making of’ videos for The Matrix, creators shamelessly admit they wanted to take Ghost in the Shell‘s stylish film noir settings and fight scenes and recreate them in live action. With the newest full-length film in the Ghost series, Kōkaku Kidōtai – Shin Gekijōban, released in late June and in theaters until July 17th), and a live-action version on the horizon, it’s important to look back to see what it was about the original film that turned the manga into an international favorite.

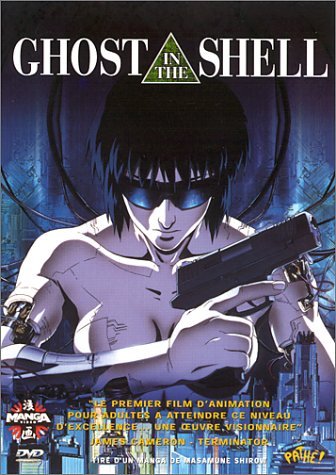

Ghost in the Shell, the 1995 film directed by Mamoru Oshii, revolves around a group of cyborg law-enforcers in the future tracking down a hacker called the Puppet Master, who hacks into the minds of unsuspecting civilians and erases their memories in the process of controlling them. One of the cops does refuse to grade-up and is 100% flesh. The protagonist is the beautiful but coldhearted Motoko Kusunagi, a cyborg cop and one of a handful of heroic female protagonists in anime.

But that’s not to say it doesn’t cater to the male sexual fantasies many have about robo-cop girls in the future. Viewers might be a bit puzzled after one of Kasunagi’s final fight scenes in which she celebrates her victory by tearing off her clothes (the film claims it allows her to scan the room, but it doesn’t explain the two other times she fights criminals naked). It does vary from similar western sci-fi films in that Kasunagi is never treated like a damsel in distress requiring someone like Neo to save her, but it’s hard to ignore the suspicion that director Oshii is simply giving viewers that dreamlike fantasy they unknowingly coveted in Japan’s workaholic society. It’s suggested in Roger Ebert’s 1996 review of the film that Japanese salarymen become so exhausted and dehumanized by the 80-hour work weeks that they “project both freedom and power onto women, and identify with them as fictional characters.”

Aside from the cop chases and virtual missions Kasunagi embarks on within the minds of those possessed by the Puppet Master, the deeper question the film’s moody plot somewhat attempts to ask is whether robots should start being considered human. Most of the conversations between Kasunagi and Batou (Kasunagi’s friend and fellow cyborg-cop), consist of debating whether their ability to think makes them human, think Descarte’s saying “I think, therefore I am.” Thankfully Ghost in the Shell throws in a couple one-liners to make sure it never takes itself too seriously:

Motoko- “Sure, I have a face and voice to distinguish myself from others, but my thoughts and memories are unique only to me, and I carry a sense of my own destiny.”

Batou- “You’re treated like other humans, so stop with the angst.”

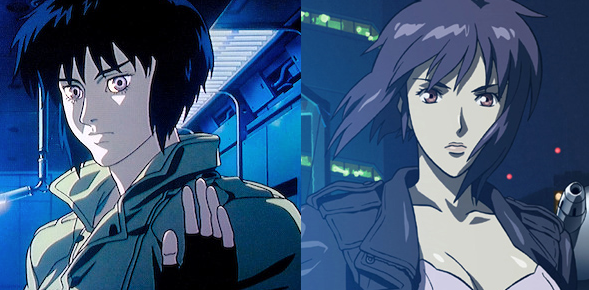

Much like Akira, the draw of Ghost in the Shell is the stunning and complex drawings of the futuristic city. In daytime scenes, it looks orange and very much apocalyptic. However, when Kasunagi enters someone’s mind or tracking someone at night, the futuristic scenery seen in Gundam and Akira takes center stage. However, one thing that distracted me from the beautiful futuristic settings were the eyes of the characters. In both this and Akira, the eyes are much more akin to those in a western comic book, rather than more recent anime that give characters blocky, rectangular eyes. The more realistic character designs create the effect of each character having a certain ‘fleshiness’ to them. This is great if the main focus over the top violence and sexiness, but I believe it reduces some of its artistic merit. The extra contour lines provide more opportunities for limbs and blood to go flying in the fight scenes, but it does so at the expense of placing characters in an uncanny valley of halfway between realistic and cartoony, thereby taking viewers out of the experience. Just as we increasingly demand our fruit to lack any blemishes or obscurities, anime has come a long way in shrinking noses, rounding eyes and turning lips into straight lines for the sole purpose of immersing you in its universe. I once read a book on the history of cartooning that explained how we more easily identify emotions when complex facial details are taken away, and by the end you are left with blank dots and lines for faces (see Gudetama, for example).

Aside from the characters the film succeeds in its mission to create the coolest futuristic vibe that had been seen so far in anime, something that inspired many movies after it, both anime and live action.

Several Ghost in the Shell films have been made, along with the original 1989 manga and an upcoming live action film set to release in March, 2017. This live action version, directed by Rupert Sanders, will be featuring Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kasunagi. However, many took to social media to state their displeasure that a white actress is taking the role of a well-known Japanese heroine. Personally I don’t find much wrong with it considering the history of anime characters combining aesthetics of Asians and westerners. Porco Rosso, one of my favorite movies of all time, takes place in a fictionalized Italy with clearly white humans everywhere. But that doesn’t take away from Porco (the main character) being a distinctly Japanese character in how weird the anthropomorphic pig man is. As long as it can recapture that image of the rainy neon-lit streets with robo-cops fighting huge mech tanks, it won’t really matter who’s doing the killing.