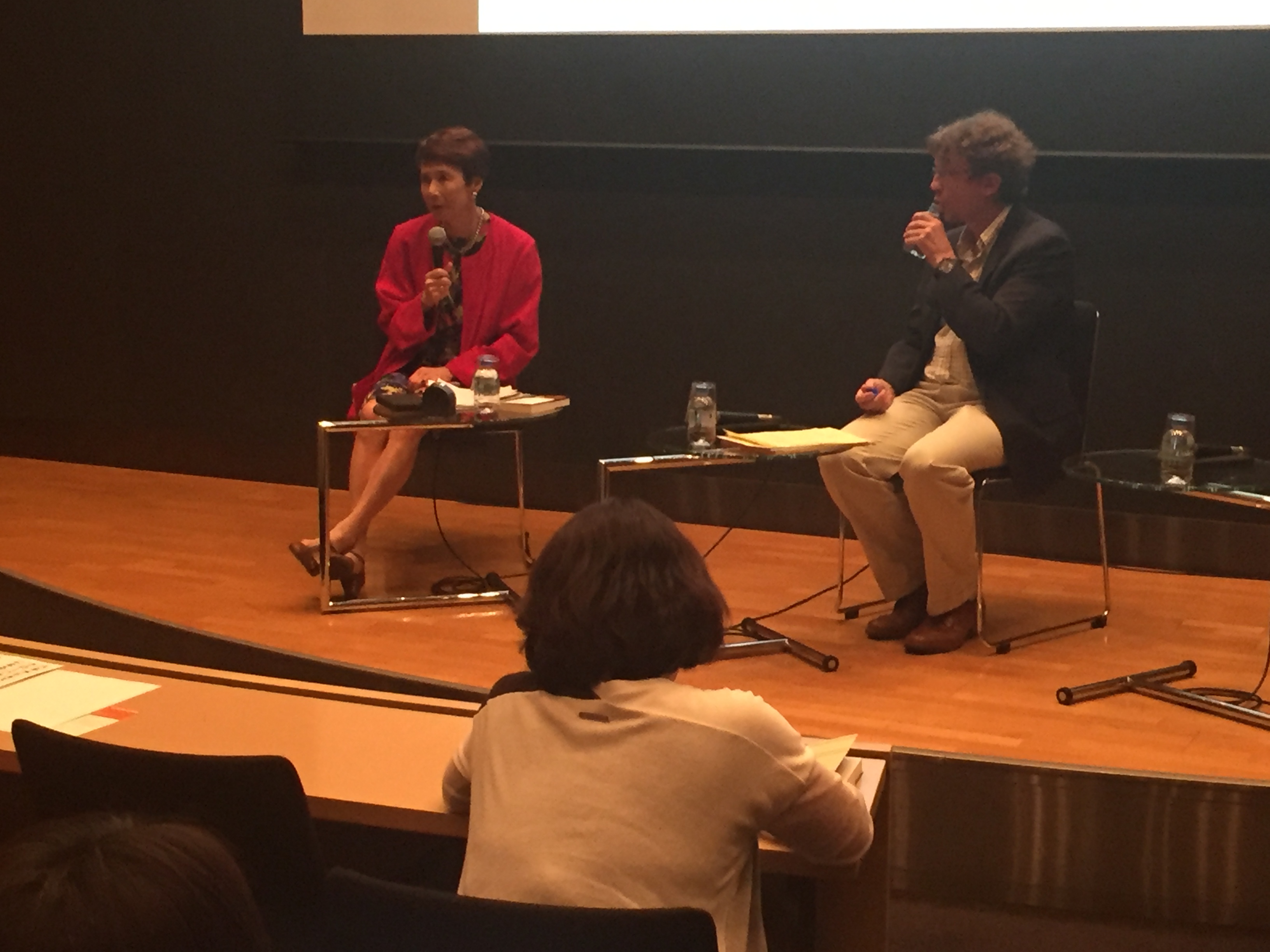

Martin Fackler, former Tokyo bureau chief of the New York Times, gave a lecture high above Tokyo at Academy Hills in Roppongi last Thursday, primarily about why Japan’s quality and freedom of the press has regressed from a world ranking of 11 to 72 since 2010 (Press Freedom Index). Filling the auditorium were around 100 mostly-Japanese journalists, students and teachers interested in getting the outsider insight on why Japanese news sources are lacking. In Fackler’s opinion, the mainstream media and their reporters have been molded by Abe’s government into thinking they are getting special access to all the country’s biggest topics, when really it’s diluting the quality of their stories. Whereas in the U.S., major sources like New York Times and BBC that are unafraid to feature public opinions that may oppose the government, Fackler says Japan’s media culture has taken the importance of so-called “access journalism” too far.

“It seems like it’s all about getting the scoop in mainstream Japan media,” Fackler said. “It’s not just the atmosphere, it’s how people’s’ careers are made, by getting the scoop to the officials’ breaking access news.”

While also praising Abe’s cabinet for their savvy when it comes to promptly addressing the media, he points out that the desire for a scoop has made newspapers such as Asahi and Mainichi regress into a routine of rarely questioning or opposing officials in their writing, since doing so would cost them their special access rights.

“Abe gives out a lot of scoops and one-on-one interviews with cooperative media members, and even has dinner with them,” Fackler said. “So if you play ball, you get a lot of access. That’s why there are a lot of ‘scoops’ in the yomiurii shimbun, sankei shimbun.”

Nowadays in Japan’s newsrooms, getting ‘scoops’ is overvalued in place of more quality journalism, i.e. going out into the field and reaching out to the officials individually in order to not get a pre-canned speech that everyone accepts as true.

Fackler also pointed to press clubs as a culprit for dumbing down Japanese reporting, something that rang true with me. When I started reporting for JSRC in Summer 2015, I noticed that a lot of the foreigners in the FCCJ rarely left the workroom to write their stories. For me, this was radically different than experiences in my hometown Baltimore, where a protest by locals in the rough parts of town was often a bigger story than the original government plan they were protesting.

“All the reporters sit there and wait for the officials to bring them news,” Fackler said. “These clubs were originally intended as a way to keep a close eye on the government, but now what they’ve become is a machine to create a very passive type of journalism. It’s not just the facts that the officials parlay, it’s also the stories, narratives and how to understand it all.”

Fackler’s opening story and example of this new “passive journalism,” was his experience initially reporting on the Fukushima disaster in March 2011. Minamisoma City Mayor Katsunobu Sakurai sent out an S.O.S. for help and almost no local reporters came in person to talk to him, Fackler being one of the few who didn’t opt to run for the hills on March 13th, one day after the disaster.

“I’ll never forget the reaction, because everyone at the front desk excitedly murmured: ‘kisha ga kimashita!’ (a reporter came!). Sakurai said the reason there was so much commotion was that all the Japanese reporters had left. So while all the mainstream papers were saying ‘The government has everything under control, don’t exaggerate the risks, etc.’, those reporters were themselves running for the hills,” Fackler said. “It became a lesson to me of how the media here has a tendency to repeat the official mindset, even if they believe differently, and that there’s a pressure to not deviate from the official narrative.”

In my opinion, much of what the former correspondent listed as the deep issues with Japan’s newspapers are easily fixable, it just takes some sacrifices with losing favor in the government’s circle of media it likes. I appreciated how Mr. Fackler took notice of NHK broadcasts constantly being focused around an official or prosecutor’s good work, never a simple salaryman or artist. Newspapers are just as much to blame for Japan’s fall in press freedom as Abe and his regime, if not more because of the power I believe news articles can have in rallying people to pressure the government into doing what’s best. Instead, we see newspaper writers falling into line like they are simply mere kohai (second rank) to the government that tells them what’s important.

“I think the Abe govt. has raised the bar with dealing with press, but the problem is the big media haven’t followed. They’re still in this post-war heiwagyou case thing, where they’re so used to having stories fed to them, that when the government roughs them up a bit, they’re like dogs and roll over on their backs. I don’t think they know or have had a good fight with the government in a really long time.”