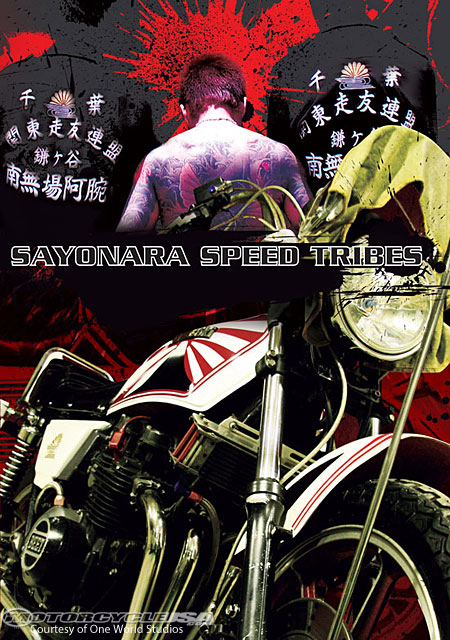

A form of Japan’s subculture is in danger of extinction–its motorcycle gangs. An independent production company, FIGURE8PRODUCTIONS, has released a documentary movie by director Jamie Morris, SAYONARA SPEED TRIBES (A Bosozoku Documentary) which poignantly immortalizes the so-called Speed Tribes, aka the bosozoku (暴走族) and captures them as they fade away into the past.

During the 1960s, in what was considered one of the world’s most conformist nations, groups of juvenile delinquents started to gather together and form large motorcycle gangs. They were first known as the kaminari-zoku (雷族) or the “Thunder Gangs,” terrorizing the local population and making enough noise to piss everybody off. They were the kids who had fallen through the cracks of the new Japan.

According to the film’s director, the term bosozoku (暴走族) was created by the media in June of 1972. “While reporting on a gang fight involving bikers in front of a train station in Toyama, a local television station from Nagoya combined bousou (暴走) “joyriding” with zoku (族) “tribe.” The bou (暴) in bosozoku means “violence, to act violently” and shares the same character as boryokudan (暴力団) aka “violent groups”– the police term for the yakuza.

The bousou-zoku, or the “Speed Tribes,” became well-known for riding noisy customized motorcycles, kamikaze warrior looks and for their bloody battles against rival speed gangs. Many of them had elaborate uniforms which they called tokkofuku (特攻服) –a nod to the stylized outfits Japan’s kamikaze pilots wore to their deaths.

The number of bosozoku reportedly went up to 42,510 in their peak period around 1982. The bosozoku were almost always under the legal age of 20, and showed various signs of anti-establishment attitudes and lack of respect towards authority. Many dedicated members ended up becoming low ranking yakuza members.

Sayonara Speed Tribes focuses on Hazuki Kazuhiro, the former leader of the Narushino Specter Gang. When the film starts, all we know is that he is currently a boxer and he is struggling to mentor a new generation of gang members and keep them riding. However, he finds that the new recruits lack enthusiasm, stamina, and time.

The documentary is part historical document but also a poignant meditation on living in the past—or survivor’s guilt. The bosozoku wanted to be kamikaze, to blaze out while young, to have a purpose–they were like soldiers with no war to fight and nothing to fight for–so they fought each other and sometimes the police.

In the opening lines of the film, Hazuki, recites a poem much loved by the motorcycle gang members at the time, and embroidered on their jackets.

Couldn’t wait around,

I had to live

For me life blossomed when I was 15 or 16

I’ll never forget those who cried for me

Women’s faces burned forever in my memory

I go through life at full speed without regret….

That’s the road I chose.

Send me to juvenile prison

Bring it on

Catch me if you can.

Specter is my crew…Specter forever

It’s a sentiment that is a lot more poetic than “live fast, die young, leave a good-looking corpse”–but not so far removed. Hazuki notes that “forever” is a lot shorter than he imagined.

The film is punctuated by a vibrant Japanese shamisen (三味線)soundtrack, and crude black and white animations of the motorcycle riders as they were, and the police and bystanders. It gives the film a feeling like one was reading a manga that periodically turns into a 3D film.

The film is not simply a documentary about the bosozoku now but poses a question for an unforgiving Japanese society: what do you do if the prime of your life was really when you were 16-18 but in those golden years, you consumed your chances to integrate into society in a fiery rage?

You can also see why the speed tribes made such a great transition into the yakuza–the same mentality, the colors, the leader, the fighting.

From all angles, the Speed Tribes are examined, and a surprising delightful interview with an officer at the National Police Agency, gives insight into the grudging respect and almost playfulness that exist between the cops and the gangs–or that used to. His explanation of why the cops no longer speed after the motorcycle tribes, appearing to let them get away is succinct and almost tongue in cheek. In almost exceedingly polite Japanese, he lays it down on the line. Cameras do the work now, no police chases needed. Unlike the old days, the motorcycle gang members don’t have to be caught in the act–the evidence taken on video is enough to find them, revoke their license, and arrest them.

The film revolves around Hazuki but there are some things left unexplained. The missing finger of the protagonist is one of them. You get glimpses of his post bosozoku life, and his new life as a yakuza where he drunkenly admits,“I was too soft to be a loan shark.” And then in a dead-on impersonation of a middle-aged businessman, mockingly repeats the lines he must have heard too many times before, “I was just on my way to pay you” and adds his own commentary.

There are scenes of photograph brilliance, where a tapestry of uniforms, the sea, and the sun are shown for seconds communicating a nobility to it all that’s close to yugen (幽玄)”mysterious beauty.”

At times the film, brushes over the fact that these gang members were more than just rebellious teens, they killed each other, some were involved in gang rape, they extorted money from the local merchants—many were violent sociopathic criminals.

By the end of the film, Hazuki’s no longer boxing but is still in the yakuza. He tries to leave the yakuza by joining a religious group, believing that the yakuza, with their Shinto roots, will understand his spiritual quest. He becomes an adherent of the Tenrikyo faith. He’s no longer wearing his Specter robes but towards the end of the film as he speaks wearing his Tenriyo– ornately decorated black robes with tendril-like white stripes, one can’t help wondering if he hasn’t just changed one uniform for another. A new oyabun, a new life, a new tribe.

He’s slowed down to discover he’s a man without a tribe and even though he’s found a new one; he’s still lonely. He has no place to call home. In his room, where the Tenri-Kyo symbol is placed on the wall, behind it are still his Specter stickers and those of another motorcycle gang gokuaku (極悪) “supreme evil.” He still thumbs through his old photo albums, and at night he wanders alone, sometimes posing the empty gang jackets in front of shrines, stuffing the arms with balloons, so the jackets convey the macho outline of a biker.

Sayonara Speed Tribes is a very good documentary on the bosozoku, although it is soft on depicting the damages done during their most violent era. It gives a great insight into Japanese culture, law enforcement and role-playing in Japan. However, the movie lingers with the viewer for many other reasons. It’s a meditation on the sadness of life alone after having once belonged to part of a bigger group that gave your life meaning and solidarity with others. The film captures the angst of being the last man in your tribe and having nowhere left to go, nor anyone interested in sharing your legacy. But if you watch the credits until the very end, you may find yourself smiling a little as you see that maybe Hazuki has at least found someone to share an interest in his past.

The film is available here at Figure8Productions. Support independent film-making and buy directly from them if you can.

ファンタジー世界

Just finished the documentary and I have to say I’m quite disappointed. The documentary is more about Hazuki than it is about the bosozoku. Hazuki is interesting and a more in depth portrait of him would absolutely be worth to watch.. But i got the documentary to learn more about the bosozoku and I don’t feel that the movie delivered in this regard. It feels like the interviews with Hazuki just scratch the surface and as the post above says there are a lot of unanswered questions..

I was watching the document and all of the sudden it was over.. I actually wondered if I by misstake ordered a promo version with a shorten version of the documentary…

I just watched it on Tubi. I thought it was pretty interesting, especially the main character going off to join Tenrikyo. I found it a bit disturbing though that he then went to Kenya and promoted his street gang. Needs a follow up.