Japanese women are angry.

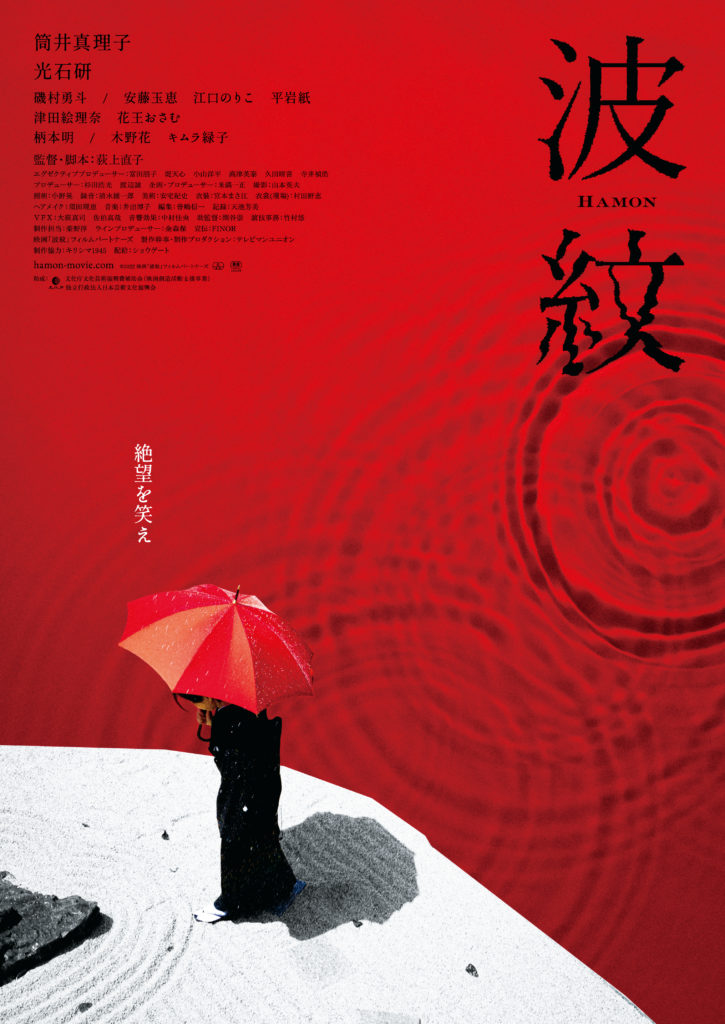

If you didn’t already know this you probably shouldn’t be reading a review of The Ripple because you won’t be interested in a film about older, enraged Japanese women.

Underneath that calm exterior made even more inscrutable by the masks that the majority of Japanese women over 30 still (still!) insist on wearing despite government mandates practically begging people to take them off, brews an angry storm that can never be appeased. NEVER. And if you were unaware of this scary fact or just assumed Japanese women were real-life versions of your favorite anime cutie, this film has very little to say to you.

But if you’ve made it this far and still sticking around, you may have felt or witnessed or otherwise become familiar with the typically silent, simmering rage of an older Japanese woman. Yoriko (Mariko Tsutsui) the protagonist of The Ripple embodies this anger to perfection. She is a woman in her late 50s who has bled out a wide tract of her life caring for husband, father-in-law and son, in varying orders, in a society that has expected nothing less and is now demanding more from her. Yoriko is enduring the physical chaos of menopause while contending with the emotional turmoil of the sudden return of her husband Osamu (Ken Mitsuishi), who walked out of their house one day over a decade ago.

Yoriko was left to deal with Osamu’s senile father, the care of their teenage son and a house in the Tokyo suburbs. Six months previously, the father had finally died in a nursing home. Their son Takuya (Yuto Isomura) had chosen a university and a job in Kyushu, far away from the capital.

“I’m feeling sorry that I left. I just wanted to light some incense for my father,” offers Osamu. And then, when Yoriko is unresponsive, blurts out that he has cancer. Yoriko finally speaks: “You’re staying for dinner?” He nods, eagerly, and appreciatively slurps down the miso soup she made.

Osamu has a lot of catching up to do in terms of getting to know his wife again. But like so many men of his generation, he can’t be bothered. The man is capable only of communicating his needs and waiting for his wife to fulfill them. A home-cooked meal. A warm bath. A clean room with a bed. Someone to sit down with at the kitchen table as the TV drones on.

Osamu also wants a hefty amount of cash for his cancer treatments.

Yoriko for her part, had spent the better part of a decade isolated and alone. She had converted her garden (which apparently once held plant life and flowers) to a dry landscape filled with jagged black rocks and blindingly white gravel. She is deeply committed to and entrenched in a religious organization that peddles “magical” bottled water. It’s expensive AF, but Yoriko has hoarded bottle upon bottle of the stuff and treats herself to a glass every night. For Osamu, she fills a cup with water from the kitchen faucet and informs him that she made her father-in-law write a will in her favor, and that she’ll have to think about helping him with his treatments.

Osamu is dumbfounded. But he lacks the communication skills to confront her or try for a reconciliation. “Please, please help me,” he says desperately as Yoriko watches him impassively.

Women like Yoriko are not uncommon in Japan—they are perhaps the norm. It’s little wonder that there’s a long tradition here of men handing over their salaries to their wives immediately upon marriage. Women control the family finances because everyone assumes that wives are bound to become miserable after 15 or 25 years of marriage. Husbands are expected to assuage the pain of their wives by paying it forward, so to speak, Marriage then, becomes a contract of financial control buttressed by mutual and permanent discontent.

Yoriko’s only friend is a janitor woman in her 70s (the always remarkable Hana Kino) who works in the same supermarket as her. “Your husband came home? Make him pay for all the suffering he caused you. Don’t show pity. Get your revenge!”

For his part, Osamu has no defenses. In one scene, he wanders over to an outdoor soup kitchen and a homeless man says to him: “You know what? You resemble a praying mantis. The male is eaten by the female during sex.”

Wow.

At this point, I feel an urgent need to discuss Naoko Ogigami, who wrote and directed The Ripple. Ogigami has told stories about Japanese women who push back against Japan’s legendary rigid patriarchy, but not in a spectacular way. More like quiet-quitting their lives as Japanese women and moving on to become their own persons.

Ogigami’s breakthrough movie Kamome Shokudo (2005) was about a 30-something woman who leaves the archipelago for Helsinki, Finland. There, she opens a diner and invites two other women (one in her 40s and the other in her 50s) to join in as staff.

This plot may not sound like much but at the time, Kamome Shokudo was blindingly new and infinitely hopeful, opening a window into a world where women did not have to be pretty or desirable or want intimacy. For these things led to marriage with its sh*t-ton of obligations and responsibilities, and it just wasn’t worth it—thanks but no thanks. By moving abroad, the Japanese woman could also avoid the flip side of the gruesome trap coin, which is caring for dementia-ridden parents at home as a single, middle-aged daughter.

Kamome Shokudo made it clear that if Japanese women were to live on their own terms, it was best to leave the country. It was a soul-crushing view of life in Japan, but for many of us it felt achingly true.

Now, 18 years after Kamome Shokudo Ogigami shows us another window into life as a Japanese woman. The Ripple is decidedly rawer and much bleaker than Kamome Shokudo, but just when you think that it can’t get any worse for Yoriko, Osamu comes through. “I’d better just die real quick,” he says and delivers on that promise. He came through for his wife in two ways: relinquishing all the money, and then exiting her life for good.

And as the undertakers carry Osamu’s body away in a casket and slips—oops!—in the rock garden, causing the casket lid to come loose and reveal Osamu’s pale dead arm, that’s when Yoriko—for the first time in the film—lets out a really joyous peal of laughter.

There’s a medical term in Japan (coined by a male doctor) called “fugenbyo,” which means “sickness caused by the husband.” The symptoms include eczema, acute depression, suicidal tendencies, aches and pains in every part of the body, hives, even cataract and blindness. Apparently you can go blind from being with a husband! It’s little wonder that Japanese women live a good 10 years longer than men because after a lifetime of doing as the patriarchy expects them to do, they sure as hell deserve some quality alone time and the means to afford it. Too bad they have to wait until their 80s.

Speaking as a Japanese woman, this is a freakishly raw deal. Count me out—I’d rather die real quick.